While the victors write the history books, in the United States, even the winners fade from consciousness, especially in the sports business. It’s a “what-have-you-done-for-me-lately” industry, and while a franchise’s front office must possess this mindset when building the best team possible, it’s also how you end up with regular people leaving Instagram comments disparaging fans of opposing teams for not winning more Super Bowls in whatever arbitrary timespan they’ve set. It’s ridiculous because, let’s take Tom Brady, for example, since he has the most Super Bowl rings of any player in NFL history; he won his seventh ring in his 21st NFL season; he spent a third of his career at that point winning championships. Now, he did come back and play for two more seasons after that, lowering the percentage, but still, spending a third of your career winning championships is something any NFL player would gladly take for their career, and yet, a third is only 33%, that’s a failing grade in academics. Winning one Super Bowl is hard enough; let’s not disparage champions just because they were unable to repeat their success; it’s why we celebrate the multiple-time champs so much rather than tear down teams who had one or two good runs.

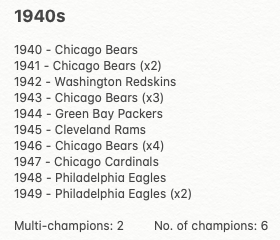

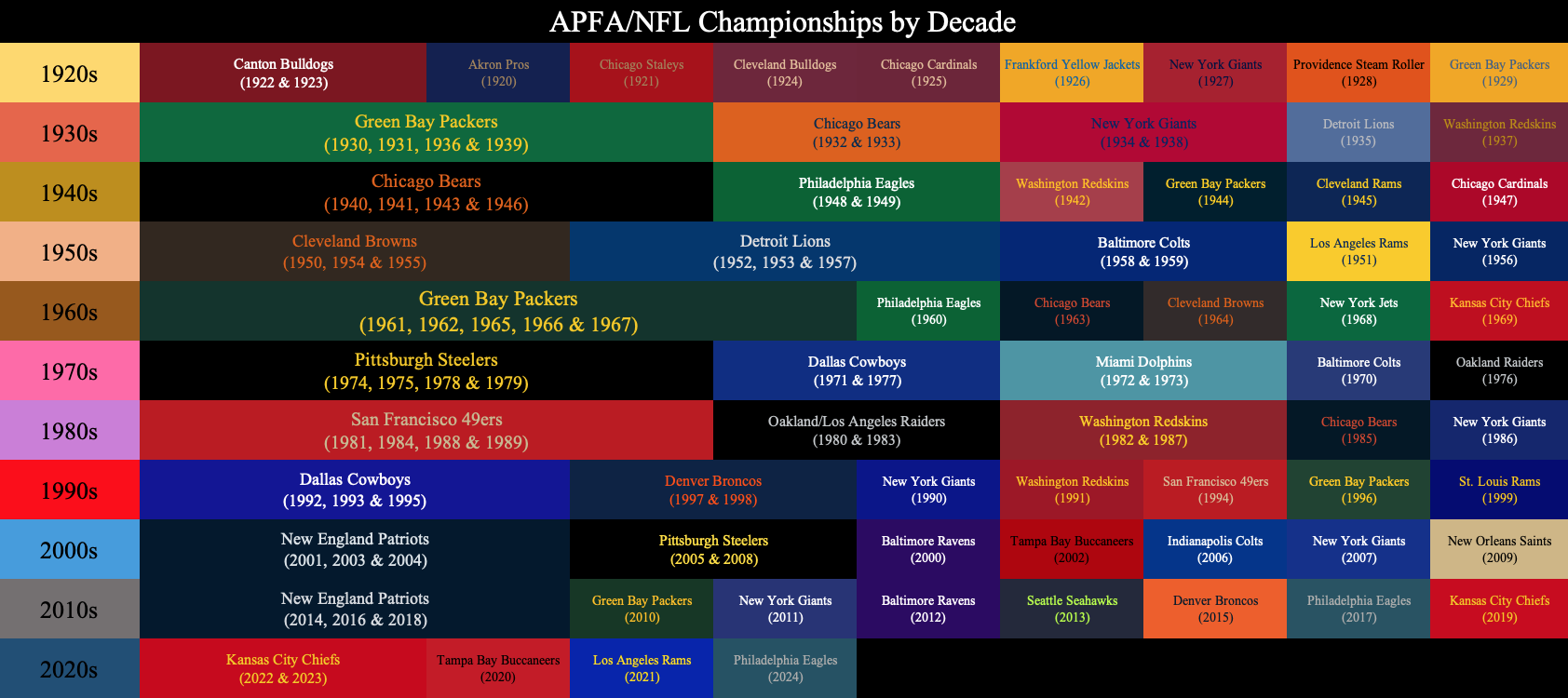

With that tangent aside, Super Bowl 59 has come and gone, and the 90th annual NFL draft will soon be upon us, but 2024 was the NFL’s 105th season of active play; there were 46 seasons of championships before the Super Bowl ever became a reality. Now, it wouldn’t be conscientious of me to skip over the fact that the first dozen seasons didn’t end with the playoffs and a championship game; rather, the NFL crowned their champion through whoever had the best regular season record based on winning percentage, with ties excluded from the formula. It was a different time, with the 1921 and 1925 championships coming with considerable controversy; while it led to undeniable champs in most of the other seasons, the system had enough flaws that, inevitably, the NFL would need to implement a postseason; for all intents and purposes, they did in 1932.

George Halas, the co-founder of the American Professional Football Association, renamed the NFL in 1922; also founder, owner, head coach, and player of the Decatur Staleys in 1920, renamed to the Chicago Staleys in 1921, before finally landing on the Chicago Bears in 1922, actively tinkered with the league and the standings in 1920, in conjunction with the Buffalo All-Americans, obfuscating the Akron Pros 1920 NFL Championship in the record books1 for 50 years. The NFL remembered the Akron Pros won the inaugural championship2 sometime in the 70s due to finding records of a vote at the offseason meeting following the 1920 season rather than relying on the standings, which they didn’t keep, as illogical as that may seem due to the formula they came up with before that season. However, Halas successfully undermined those same All-Americans to win the championship in 1921 by scheduling a rematch with the All-Americans after losing to them earlier that season and then cramming two more games in before the cut-off date to conclude the season, a win and a tie, to give his team a chance to argue their case as champions; the NFL has always upheld the Bears (then the Staleys) as the rightful 1921 NFL Champions3, due to a tiebreaker they came up with that offseason favoring the winner of the second game in the case of two teams playing more than one game against each other. Halas ultimately tried unsuccessfully to repeat a similar tactic in 1924, with the league outright stating there would be no playoff game to decide a season’s champion and that the Cleveland Bulldogs were the 1924 NFL Champions4 even with a loss to the Bears due to still possessing a better winning percentage by season’s end. I say all this not to denigrate Halas but to stress how unbridled the structure of professional football was; teams didn’t even schedule the same amount of games as each other, allowing Halas opportunities to pull off these feats.

1925 saw the infamous awarding of the NFL Championship that season to the Chicago Cardinals over the Pottsville Maroons due5 to the Maroons playing an exhibition game against a team dubbed the “Notre Dame All-Stars,” with the Frankford Yellow Jackets crying foul, stating the Maroons violated the Yellow Jackets’ territorial rights by scheduling an exhibition game that didn’t count against the standings in Philadelphia, their territorial market. The Maroons stated the league verbally approved their decision to schedule the game in Philadelphia due to them viewing their home stadium as too small to host such a lucrative event, one that would establish professional football as the highest quality form of the sport available; however, then NFL Commissioner Joseph Carr telegrammed the Maroons, warning them if they played the game, they would face suspension for doing so. They played the game anyway, won, and Carr immediately suspended them following the game; at the offseason meeting, the league owners decided the Chicago Cardinals would be NFL Champions, only for Cardinals owner Chris O’Brien to refuse the championship, stating his team did not earn it after losing to the Maroons handily earlier that season.

The following six seasons went by without any relative controversy, as whoever finished at the top of the standings had the best winning percentage and best case as champion, save for 1931 when the Packers essentially6 canceled a game to preserve their 12-2 record and first-place finish. However, in 1932, the NFL scrapped their rematch tiebreaker rule devised by Halas to determine the 1921 NFL Champion as both the Chicago Bears and Portsmouth Spartans, now the Detroit Lions, finished with six wins and one loss in 1932. The Bears finished with six ties compared to the Spartans’ four draws, but the NFL didn’t factor those into the winning percentage at the time, and the teams had tied in both games they played against each other that year. The Packers were in pursuit of their fourth consecutive championship that season, and under the current NFL winning percentage formula, they would have won it with their 10-3-1 record; once again, the NFL didn’t factor in ties, and teams scheduled their games, meaning franchises didn’t play in a standardized number of games, resulting in the Packers’ 76.9 winning percentage being lower than both the Bears’ and Spartans’ 85.7 winning percentage. That’s football, though, as under modern calculations, the Giants would have finished first over the Packers in 1930 anyway; regardless, the Bears beat the Spartans on December 18th, 1932, by a score of 9-0 at the smaller indoor Chicago Stadium, with sixty yards dedicated to the field of play while the final twenty yards consisted of both end zones.

The hastily scheduled 1932 Championship Game isn’t technically a postseason game, as it counted in the final regular season standings and determined who would finish first and third that season. However, it proved extremely popular, and along with better individual statistical tracking that season and with an upcoming set of rule changes that opened up the passing game and scoring potential, the 1933 NFL season set the foundation for the modern NFL seasonal experience. The 1933 NFL season was the first to introduce divisions and postseason, with the top two teams from each division meeting in the championship game, with a standardized number of games soon to follow in 1936, initially set at 12. Those rule changes deviated from college, greatly enhancing the viability of the passing game by allowing a forward pass anywhere behind the line of scrimmage, as opposed to requiring a passer to be at least five yards behind the line of scrimmage. The NFL also moved the goalposts to the front of the end zone in 1933 to reduce the number of ties occurring league-wide before later moving them back to the end line in 1974; they also established hash marks and the fact that all plays would start with the ball on or between the hash marks, along with touchback and safety rules regarding punts hitting the goal posts7.

Before we move on, though, let’s look over the decade when the most franchises won a championship in NFL history. Nine franchises won a title this decade out of the hypothetical maximum of 10; the NFL prides itself on its parity, but this is still the most franchises to win a championship in one decade in NFL history. The game was entirely different, with an extreme emphasis on defense and running the ball; there was no standardized schedule, and as of yet, there are no surviving recorded individual statistics beyond scoring for any player or game of this era; there wasn’t a postseason, and the skill positions that attract casual audiences were all-around ends and backs as opposed to the specialized offensive roles we have today. It was the birth of professional football, and as one would expect, it led to some wild results that we don’t see anymore in a world where the NFL brings in billions of dollars in revenue. Five of the nine franchises who won a championship in the 1920s aren’t even around anymore, but perhaps you’ll find solace in the fact that the Pro Football Hall of Fame resides where the first NFL franchise to become multi-champs and win back-to-back championships played; Canton, Ohio.

There is one final person worth reflecting on for their accomplishments this decade, as while it’s fair to say no team was a dynasty in the 1920s, there was one man who was a dynasty all to himself in Guy “Champ” Chamberlin. Starting as an end for the Decatur Staleys in 1920, he became one of the central figures of the 1921 Chicago Staleys championship team, being fourth on the team in scoring that season. Following the title win, however, Chamberlin carved a different path towards football immortality, becoming a player-coach from 1922 to 1927; in those six seasons, his teams won the championship four times. I stress the word “teams” as he played and coached with four different franchises in that six-season timespan. Chamberlin was the coach of those Canton Bulldogs, and then after their dissolution, won the championship the following season with the Cleveland Bulldogs, joined the Frankford Yellow Jackets in 1925 and won the title with them in 1926, and then retired after one poor season with the Chicago Cardinals in 1927 at the age of 33. He died in 1967 and, a couple of years later, was retroactively and posthumously named to the NFL 1920s All-Decade Team in 1969. I can’t recall the last time I heard Chamberlin’s name mentioned in a casual football discussion, but he’s a legend in the pantheon of football history, should anyone choose to browse that section.

The 1920s are a fascinating time to look back on in NFL history, as the APFA had quickly rebranded to the NFL in its third season, placed the professional game on a higher level than the college game in its sixth season, and as a result of the way the NFL owners handled the 1925 championship controversy, consequently created its first major competitor when the agent of the Chicago Bears star halfback Red Grange announced the creation of the American Football League before8 the 1926 season. The NFL added two new franchises to provide even more competition for the upstart AFL in 1926, but it proved fruitless as their competition folded after the season, and the NFL contracted down to 12 teams to start the 1927 season. There were 14 franchises for the inaugural 1920 APFA season, 21 in 1921, 18 in 1922, 20 in 1923, 18 in 1924, and 20 in 1925, so this contraction was troubling. Despite the success of the young league, professional football was still not the billion-dollar behemoth that it is today, and the owners of the small-town teams found this out as they lost money owning a pro team, dying off even before the Great Depression hit. It’s hard to believe, but in the NFL’s formative years, professional football wasn’t an extremely lucrative endeavor.

The NFL kept the franchise total around that number for what little remained of the decade but for the entirety of the 1930s as well. It dipped from 12 to 10 from 1927 to 1928 but went back to 12 in 1929 before falling to 11 franchises in 1930; this spotty franchise membership trend continued throughout the decade. The number of franchises never dipped below eight but never rose above 12 throughout the 1930s; it makes sense then why the teams that currently consist of three-quarters of the NFC North dominated the championship total throughout the decade, winning seven of the ten championships that decade, with two teams consisting of half the current-day NFC East winning the other three. Being five of the six oldest teams in the NFL has its perks. However, by the time the 1930s ended, nine current-day NFL franchises were in the league, with the newest one, the Los Angeles Rams, then known as the Cleveland Rams, joining play in the 1937 NFL season.

The forward pass showcased its dominance this decade, as Curly Lambeau’s Green Bay Packers won four championships in the 1930s on the strength of his Packers’ passing attack. Don Hutson joining the Packers in 1935 was a turning point for the franchise, as the two championships they had won earlier in the decade had come before the 1933 rule changes and under the old format of awarding teams the title based on their record; at that point, the Bears had won back-to-back in 1932 and 1933, while the Giants won in 1934, the same year as the first 1,000-yard rusher in NFL history, with halfback Beattie Feathers of the Chicago Bears earning that distinction. The newly christened Detroit Lions won in 1935, the Packers’ first year with Hutson, but that first year saw the Packers’ defense improve from 7th out of 11 in 1934 to 1st out of 9 in 1935, and their record improved by one win, 7-5 to 8-4. Their offense remained third in the league, but they averaged 3.1 more points per game in 1935 with a rookie Hutson than they did in 1934, and this core gelled together to a 10-1-1 record and an NFL Championship in 1936 behind the number-one scoring offense that season. Hutson led the NFL in receiving touchdowns and receiving yards per game his rookie season but stepped up even more in 1936, leading the NFL in receptions, receiving yards, receiving touchdowns, yards per reception, and receiving yards per game; he’d repeat this feat one more time, in 1939 when the Packers won their second title with him during the decade, but he’d lead the NFL in receiving yards and receiving yards per game six more times and receptions and receiving touchdowns seven more times before retiring after the 1945 NFL season.

However, while the Green Bay Packers were the team of the 1930s, having won the most titles that decade, it’s worth noting that the Bears did prevail in that previously mentioned 1932 NFL Championship Game, although it’s not known as that. The Bears also prevailed in a classic back-and-forth game with the Giants the next season in the official inaugural NFL Championship Game, 23-21, complete with a game-winning touchdown in the last four minutes and a critical defensive stop to secure the Bears’ back-to-back championships and third title overall9. Those same Giants prevailed over the Bears the following season, this time being the ones to mount a fourth-quarter comeback, although with much less dramatics. The Bears had a 10-3 halftime lead and were leading 13-3 lead entering the final quarter of the 1934 NFL Championship Game, but the Giants furiously stormed back; after switching to basketball sneakers10 for better grip on the icy field at halftime, they scored 27 points in the fourth quarter to end the game with a 30-13 final score, forever cementing the game as “The Sneakers Game.” The Giants intercepted the Bears three times out of the Bears backs’ 15 total pass attempts; star fullback Bronko Nagurski scored the Bears’ only touchdown with a one-yard rush in the first quarter and was the only Bear to throw a pass this game without being intercepted, although to be fair, he did throw only one pass all game.

Lambeau’s Packers were not the only team to utilize the forward pass this decade, as the 1937 Washington Redskins beat the Chicago Bears for the championship that season, due primarily to the explosiveness of who would become one of the premier players of his era for what would eventually become the quarterback position; Sammy Baugh. Packers’ tailback Arnie Herber was the first player to throw for 1,000 yards in a season in 1936, finishing with 1,239 passing yards that season, but Baugh threw for 1,127 the very next season and led the NFL in that statistic; in his rookie season no less, while also rushing for 240 yards; the future of the sport radiated from Baugh as he threw two touchdowns in the 4th quarter of the 1937 NFL Championship Game to pull ahead, 28-21, and eventually win, finishing with 335 passing yards and a 107.5 passer rating. The forward pass aided Baugh and the Packers in ’36 and ’39; it worked against the Packers in 1938, however, as the New York Giants, who had rebuilt their suffocating defense to return to the elite class of the league, were the ones to throw a go-ahead and eventual game-winning touchdown pass in the 4th quarter of the 1938 NFL Championship Game against Lambeau’s Packers. If not for the Packers returning to the Championship Game the next season and thrashing the Giants 27-0, there could be legitimate arguments for who the team of the 30s was. There was a slight distinction in win total between the elite teams and the good ones, as the Bears finished with just one fewer regular season win than the Packers during this decade, but make no mistake, the five champions of this decade dominated the overall win total over the temporary, newly established, and just downright struggling franchises.

World War II officially began with the Invasion of Poland on September 1st, 1939, which saw the United States adopt a policy of neutrality. Despite this, the United States did supply the Allies with materials and stationed men in Iceland at British request. After the USS Greer incident on September 4th, 1941, the United States became active naval aides during the Battle of the Atlantic on September 11th, 1941, but weren’t directly involved in battle with the Axis until the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor on December 7th, 1941. What does any of this have to do with professional football? Quite a bit in the coming years, as we’ll soon see.

While World War II raged across the pond, Halas and the Bears were reintroducing the T-formation to professional football. Second-year quarterback Sid Luckman and sending a man-in-motion were more relevant than Adolf Hitler and the Nazis in the first two seasons of the ’40s, as the Bears used these concepts and their star power to cruise to back-to-back championships in 1940 and 1941. While the Redskins possessed the best record in 1940 at 9-2, they wound up losing to the Bears in the 1940 NFL Championship Game by a still-record margin; 73-0. Lambeau’s Packers matched the Bears’ record the following season at 10-1, necessitating a tie-breaking playoff game between the two teams for the right to compete against the Giants in the 1941 NFL Championship Game. It’s important to note that the tie-breaking playoff game was introduced as the Divisional round of the playoffs, eventually morphing from a simple tie-breaker game played only if necessary to a full-fledged round of the playoffs. The Bears beat the Packers, 33-14, and then went on to defeat the Giants a week later, 37-9, securing their position as the best team in the league. The NFL would undergo significant changes that off-season, however, as the previously mentioned Japanese surprise attack on Pearl Harbor occurred just a week before the Divisional Playoff game and two weeks before the season wrapped up with the NFL Championship Game.

According to various sources11, over 600 NFL players joined the United States military following the 1941 season; even George Halas left the Bears midway through the 1942 season to join the Navy. The Redskins retook their place as second-best in the league, as their defense improved back to a top-three unit, sporting a 10-1 record by the 1942 season’s end, with the Bears finishing first once again, this time boasting a flawless 11-0 record even without Halas. It was for naught, as the Redskins prevailed against the Bears, 14-6, in the Championship Game. Baugh out-dueled Luckman in a low-scoring game where Baugh’s go-ahead second-quarter touchdown pass wound up being the only score needed to hold off the Bears; a third-quarter touchdown drive capped off by a one-yard touchdown run from fullback Andy Farkas was the cherry on top of a spoiled perfect season while simultaneously being a nail in the coffin for the Bears attempt at one. However, it’s worth stepping aside to examine the rest of the field for a moment.

While the total number of teams remained the same in 1942 as in 1941 with 10, and they all still played the agreed-upon 11 games, only four teams had an above .500 record that season as opposed to five in 1941. That doesn’t sound like much, but one of those teams below .500 included an 0-11 season by the talent-depleted Detroit Lions, the first winless season league-wide since the Cincinnati Reds went 0-8 in 1934. If we want to be more optimistic, at least 1942 can claim the NFL’s first 2,000-yard passer in a season, Cecil Isbell of the Green Bay Packers, with 2,021, while Don Hutson became the first player to record 1,000 receiving yards this same season, finishing with 1,211. Isbell’s record didn’t last long, falling the ensuing season, but nobody threw over 2,000 yards in a season again until 1947, when three quarterbacks accomplished the feat; two quarterbacks accomplished the milestone in 1948 before closing the decade with three quarterbacks again registering 2,000-yard passing seasons. However, as far as quality of competition, 1943 may have been worse, as the league contracted to eight teams, with the Eagles and Steelers temporarily merging into one team this season and the Rams suspending operations for the year. Teams now played ten games for the season, and while five teams were above .500 in 1943, the Chicago Cardinals went 0-10, and the best of the remaining three teams topped out at .333 percent. Still, a divisional playoff game needed to be played between the 6-3-1 Redskins and Giants to decide who would once again face the 8-1-1 Chicago Bears in the Championship Game.

It’s worth noting that Sammy Baugh led the NFL in pass completions, interceptions, and punts in 1943, earning him the distinction12 of a “triple crown,” which is highly unlikely to be replicated again, considering the highly specialized nature of each position in the current-day NFL. That highly specialized nature of each position began formulating this season; in response to the depleted rosters from World War II, the NFL adopted a free substitution policy, changing the nature of the game forever. In the past, the expectation was to play on both sides of the ball for the game’s entire duration, so if a player subbed out between plays, he was ineligible to return for the quarter. It used to be even more draconian, as that player couldn’t return for the entire half until 1932. Free substitution was renewed the following two seasons before having a three-men-at-a-time maximum substitution restriction rule from 1946 to 1948; free substitution returned in 1949 and was made permanent in 1950, marking the death of the one-platoon system in professional football.

The Redskins dismantled the Giants, 28-0, and then received the same treatment in return the following week, with the Bears enacting their revenge for the Redskins spoiling their perfect season the year prior by winning 41-21. Baugh may have won a “triple crown” this season; Luckman led the NFL in passing yards, passing touchdowns, yards per attempt, and passer rating, all by wide margins, with his 107.5 passer rating being utterly unfathomable by 1943 standards. It was more of the same this day, as Luckman threw for 286 yards, five touchdowns, and no interceptions en route to the 20-point victory, securing the Bears’ third championship in four seasons and establishing the Monsters of the Midway as a dynasty.

Allied forces had already stormed the beaches of Normandy, liberated Paris from Nazi Germany, and were bringing the successful Operation Overlord to a close by the end of August 1944. Their campaign on the Siegfried Line began shortly after, so when the Green Bay Packers started week 1 of the 1944 season at home against the newly-renamed Brooklyn Tigers, Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery had already begun Operation Market Garden with the Battle of Nijmegen earlier that day, September 17th, 1944. The tide of the war had shifted monumentally in the Allies’ favor, but the war was still active, so rosters remained depleted for another season; the Eagles and Rams resumed operations, but the Steelers merged with another team this season, the Cardinals, becoming Card-Pitt. The name doesn’t possess nearly the same ring as Steagles, and it showed on the field, becoming one of two teams, the other being the earlier-mentioned Brooklyn Tigers, to go 0-10 for the season; back-to-back seasons with winless franchises, this time now with two, isn’t exactly glowing praise for the standard of competition during this roster-bleeding time. Regardless, the Giants put together another strong season, finishing with the best record in the NFL at 8-1-1 behind their first-ranked defense.

Chicago, however, was seemingly focused more on the war efforts than worrying about repeating as champions. Sid Luckman volunteered for military service following the 1943 season and only played in seven games in 1944; all-in-all, 45 members of the Bears’ organization volunteered for the war effort13 during this period, with the 1944 and 1945 teams being the two most clearly impacted by this approach, as the Bears went 6-3-1 in 1944 and 3-7 in 1945. This course of action opened the door for the team that had been a step behind them for the last four seasons, Curly Lambeau’s aging Green Bay Packers.

They took full advantage of a weakened playing field, going 8-2 on the season, with Don Hutson leading the NFL in receptions for the penultimate time of his career, ironically his penultimate season, while also leading in receiving yards, receiving yards per game, and receiving touchdowns for the final time in his illustrious career. The Packers met not only those Giants at the frigid Polo Grounds for the championship but also their former tailback Arnie Herber, who came out of retirement this season to help keep operations running smoothly for the fifth-ranked offensive unit in football since 1942. However, the Packers’ third-ranked offense jumped out to a 14-0 lead at halftime and then relied on their third-ranked defense to maintain it; they yielded a one-yard touchdown run early in the fourth quarter but held on to win 14-7 for Lambeau’s third championship of the playoff era and his sixth and final championship overall.

The old guard had snuck out a championship under favorable circumstances, but a new epoch had already materialized around them. The Cleveland Rams, who suspended operations in 1943 and went 4-6 the previous season, drafted quarterback Bob Waterfield and paired him with end Jim Benton, who they got back for the 1945 season from the Bears. The result was explosive, with Waterfield leading the NFL in passing touchdowns and passing touchdown percentage, Benton leading the NFL in receiving yards while becoming the second receiver in NFL history to crack 1,000 receiving yards in a season with 1,067, and the Rams finishing third on offense and defense and first in the NFL with a 9-1 record.

Sammy Baugh led the NFL in pass completions, completion percentage, and passer rating, setting the NFL record for passer rating in a season with 109.9, bolstered in large part by those stats but also his 11 passing touchdowns to four interceptions ratio. His leadership and excellent play, in part with the Redskins’ defense returning to first in the league, buoyed the Redskins record to 8-2, resulting in an inevitable showdown with the Rams for the championship. The game itself was controversial, as Baugh committed a self-safety in the first quarter; the Redskins had the ball at their five-yard line when he dropped back to pass into the end zone and hit the goal posts, which were still at the front of the end zone at the time. If a pass attempt hit the goalposts at this time, the NFL indeed ruled it a safety, which gave the Rams a 2-0 lead; to make matters worse, Baugh was injured in the second quarter and replaced with backup Frank Filchock. Or so it seemed, as Filchock threw a 38-yard touchdown pass to Steve Bagarus to take a 7-2 lead. Filchock was 8-for-14 with 172 passing yards, two passing touchdowns, and two interceptions to finish with a 100.9 passer rating while stepping into the most high-pressure situation a team can be in. It wasn’t his fault the Redskins came up short, as while he did throw two interceptions, the Rams came to life with Waterfield throwing two touchdowns, one to Benton to take a 9-7 lead at halftime and one to Jim Gillette, but he missed that extra-point attempt to take a 15-7 lead in the third quarter.

Filchock led a scoring drive before the end of the third quarter, throwing his second touchdown pass to Bob Seymour, cutting the deficit to one, 15-14. However, that wound up being the final score of the game, and while one can question why you can’t say it’s not Filchock’s fault for coming up short for throwing two interceptions, it’s worth pointing out Redskins’ kicker Joe Aguirre missed both his field goal attempts for the day in the 4th quarter, denying the Redskins their chance for their third title14. However, Redskins’ owner George Preston Marshall was instead incensed by the safety ruling, and it’s hard to blame him as despite the missed field goals providing enough points to carry the margin of victory, the safety that, if ruled incomplete instead, would’ve also been enough points to instead ensure a one-point Redskins victory.

The NFL changed the rule15 that offseason, but the game was already over; the Redskins best chance at a championship with Baugh slipped away from them, as they never made the championship game again after this season and only had one season above .500, in 1948, by the time Baugh retired after the 1952 season. He continued posting good stats, but the Redskins were moved aside as the NFL re-filled with players returning from the war. Dan Reeves, owner of the Cleveland Rams, reportedly lost at least $50,000 during the Rams’ championship season16 and was rewarded for his efforts by being allowed to move his franchise to Los Angeles17 to avoid losing more money to what was to become the NFL’s second legitimate challenger for their throne as the top professional football league in the United States.

I use the word legitimate because I purposefully glossed over the second and third iterations of the American Football League, which, as mentioned above, was the first attempt at challenging the NFL for football dominance in the United States, way back in 1926. There were two attempts at reviving this brand, the first in 1936, which succumbed to the NFL after one season, similar to its predecessor, with this being how the NFL acquired the Rams in the first place to start play in the 1937 season. The third iteration of the AFL began play in 1940 and lasted a season longer than its predecessors before folding after the 1941 season. Neither of them was a serious challenger to the NFL’s throne, but after its founding in 1944 by Chicago Tribune sports editor Arch Ward, the All-America Football Conference, or AAFC for short, began play in 1946. Unlike the prior competitors, the AAFC enjoyed press coverage in the newspapers due to its founding by a sports editor for a national publication; Ward also made sure to use the best of his connections to ensure the AAFC franchises were helmed by businessmen who were already wealthy with their ventures and were fans of the sport who may have already attempted to purchase an NFL franchise before18.

I won’t go into much depth about the AAFC, however, as this essay doesn’t need to diverge too far from the history of the NFL. However, I must mention Paul Brown’s hiring by the Cleveland AAFC franchise, which shortly after renamed itself in his honor, the Cleveland Browns. The Browns were the premier team of the AAFC, winning its championship in all four seasons of its existence before the AAFC merged with the NFL on December 9th, 1949, with the Cleveland Browns admitted into the NFL along with the San Francisco 49ers, the only other consistently strong AAFC franchise during its existence. The Baltimore Colts, founded in 1948, were also admitted into the NFL but folded after its first season in the NFL before being revived under the same name as a separate franchise in 1953. Before that point, though, the Bears had to reclaim their title as conquerors of the NFL in the first post-war season.

While the rosters re-filled out with players returning from the war, sadly, 19 members of an NFL roster lost their lives during combat in World War II. The AAFC also poached considerable talent from the NFL, filling their rosters with former players and signing away players they drafted. Truthfully, in this post-war period, especially with the dominance of the military branches in the collegiate game, fans of the game once again saw college teams as superior to professional football franchises, something AAFC founder Arch Ward conceded19. Football still needed to be played, however, resulting in most of the league going 6-5 that season as the NFL returned to an 11-game schedule; besides the top two teams that season, only the Los Angeles Rams posted a .600 or better record at 6-4-1. Those two teams, the New York Giants and Chicago Bears, finished 7-3-1 and 8-2-1, respectively, and much like the Bears and Redskins the year before, met for the fourth time since 1933 in the NFL Championship Game.

It was a hard-fought game, but the Bears proved themselves as the dominant team of that era, showcasing their first-ranked offense that season with a 14-0 lead in the first quarter before the Giants responded with a touchdown before the end of the quarter. Unlike seasons past, the Bears finished with the fifth-ranked defense that season and gave up another touchdown in the third quarter to let the Giants tie the game at 14. From here, though, the Bears flexed their championship experience, exhibiting heart in the crucial moments, scoring 10 points in the fourth quarter behind a 19-yard Sid Luckman touchdown run and Frank Maznicki’s 26-yard field goal to seal a 10-point victory and their fourth championship of the decade, as well as their seventh overall in franchise history.

The adage is that imitation is the sincerest form of flattery, and it’s well-known the NFL is a copycat league; by the start of the 1947 season, nearly every professional franchise was running the T-formation, save for the Steelers, most infamously. Halas may have engineered a dynasty, but he also inspired the rest of the league, who took his concepts and, as his players aged, overtook the Bears from their position as the top team in the league. A different team in Chicago was devising a way to win a championship at any cost, as Charles Bidwill, the owner of the Chicago Cardinals, was feeling the pressure of the Bears’ success and the newly-established AAFC Chicago Rockets franchise, who threatened to cut into the Cardinals’ fan base by scheduling games at current Bears’ stadium Soldier Field, just three-and-a-half miles away from Comiskey Park, where the Cardinals played.

Bidwill purchased the Cardinals from David Jones in 1932, who bought the franchise from original owner Chris O’Brien in 1929 amidst losing seasons and struggling in popularity against the Bears. Bidwill accepted the 1925 title that O’Brien declined when he bought the team, but as of 1947, he hadn’t won a title under his ownership and had all the same problems O’Brien did when he sold to Jones in 1929. Bidwill was more interested in purchasing the Bears outright from Halas, as Bidwill was part-owner after purchasing $5,000 worth of team stock; when it became apparent that Halas would not sell the team, he bought the Cardinals and waited a year to make the sale public to give himself time to rid himself of all his Bears stock20. 1946 was only the team’s second season above .500 since Bidwill bought the team; determined more than ever to forge a championship-winning squad, Bidwill shocked the football world on January 17th, 1947, when he drafted and successfully signed collegiate star Charley Trippi away from the AAFC’s New York Yankees with a $100,000 contract. This act completed what Bidwill deemed his “Dream Backfield” but became more famously known as the “Million Dollar Backfield,” with Trippi joining quarterback Paul Christman, drafted in 1945, halfback Elmer Angsman, and fullback Pat Harder, both drafted the previous year. Unfortunately, Bidwill didn’t live long enough to see the fruits of his labor, as he passed away three months after signing Trippi on April 19th, 1947. The Cardinals eventually beat the crosstown rival Bears in the last week of the season to clinch the best record in the entire league at 9-3, as the schedule expanded to 12 games this season.

The 8-4 Eagles smacked the Steelers 21-0 in their divisional tie-breaker to match up with the Cardinals for the championship, owning the higher-ranked offense at second compared to the hyped Cardinals’ third-ranked offense. That hype was not all for naught, though, as Angsman and Trippi both had spectacular performances, with Trippi scoring early on a 44-yard touchdown run and Angsman following in the second quarter with a 70-yard touchdown run of his own. Incensed by the officials forcing his team to switch to basketball shoes to match the Cardinals’ attire21 during the icy game, head coach Greasy Neale’s team fired back, with quarterback Tommy Thompson launching a 53-yard touchdown to Pat McHugh to cut into the lead before halftime, but Trippi ripped off a monstrous 75-yard punt return touchdown early in the third quarter to take back the 14-point lead. The Eagles had molded themselves as a stingy defensive team that leaned on their tough halfback Steve Van Buren, who had already led the NFL in rushing yards and rushing touchdowns in 1945 before doing it again this season in addition to having the most rushing attempts, and down 21-7 in the championship game in a two-season stretch where their defensive unit fell from second-ranked in 1944 and 1945 to 7th in 1946 and 5th this season, they continued displaying their grit and capped off a drive with a one-yard Van Buren touchdown run before the end of the quarter. Angsman responded by roaring 70 yards down the field again for a touchdown run early in the fourth quarter to reclaim the 14-point lead for the Cardinals. The Eagles, to their credit, never gave up, scoring a one-yard touchdown run in the closing minutes to make it 28-21, but after showcasing that kind of dominance in the run game, the Cardinals were able to run out the clock and win the 1947 NFL Championship. Angsman finished the game with 10 rushing attempts for 159 yards and two touchdowns, Trippi had 11 carries and went for 84 yards and a touchdown, as well as 102 punt return yards and the punt return touchdown, and Bidwill’s wishes came true, even if post-mortem.

The result would not be so favorable for the Cardinals the following season. While the Cardinals offense reached the heights Bidwill originally dreamed of in 1948, finishing first in the NFL and repeating as third-best on defense, the Eagles returned to their trademark strong defensive identity in 1948, finishing second, and were more determined to win the championship after coming up short to the same team the year prior. Their offense remained second-best, and Van Buren once again led the NFL in rushing attempts, rushing yards, and rushing touchdowns, powering this unit to a 9-2-1 record, first in the East Division but third in the NFL, behind the 10-2 Chicago Bears and the West Division representative against the Philadelphia Eagles in the 1948 NFL Championship Game, the 11-1 Chicago Cardinals. In a rematch of last year’s championship game, the play on the field couldn’t have been more diametric, ending 7-0 in a blizzard with the Eagles recovering a Cardinals fumble on their side of the field and the Eagles scoring quickly after on a five-yard Van Buren touchdown run in the fourth quarter. Christman was injured and didn’t play after week eight, but they hadn’t lost a game in his absence. The difference in this game was that Angsman, Harder, and Trippi combined for 30 rushes for 89 yards, and Van Buren had 26 rushing attempts for 98 yards and a touchdown; the Eagles imposed their will and overcame the defending champions to claim their first championship. Now sitting atop the mountaintop after four years of building towards it, the Eagles took a page out of the Cardinals’ playbook and returned the following season better than ever, finishing 11-1, first in the NFL.

The Eagles were opposed this time by the retooled Los Angeles Rams, who were making their first championship appearance since moving to Los Angeles in 1946. Still quarterbacked by Bob Waterfield, the Rams drafted Tom Fears in 1948, who led the NFL in receptions as a rookie and then did it again this season in addition to leading in touchdown receptions and had himself a 1,000-yard receiving season to go along with those incredible accolades. The Rams’ record improved from 6-5-1 to 8-2-2 behind their second-ranked offense; it all came to a screeching halt in the wet, muddy conditions of their home field as the Eagles shutout a second straight victim in the NFL Championship Game, this time 14-0. They had just 119 total yards compared to the 196 rushing yards Van Buren racked up alone; the Eagles as a whole had 342 total yards, as well as a blocked punt in the third quarter they jumped on in the end zone for a touchdown to stretch it to that 14-0 lead they sat on for the remainder of the game. That’s when we smash cut back to the point I made earlier about the AAFC and the admittance of the Cleveland Browns to the NFL because, at this point, the Philadelphia Eagles have made their case as the premier team of the NFL, closing the decade with dominant back-to-back championship performances; the Browns had been practically begging the NFL to allow them the chance to prove themselves against their champions22 since they won the inaugural AAFC championship in 1946

Before fully jumping into the 50s, let’s once-over at the turbulence of professional football in the 1940s. Just going off the few statistics provided earlier in this essay shows a sizable percentage of the NFL was off fighting a war overseas, a concept incredibly foreign to us today, no doubt impacting competitive parity throughout the decade. The Bears ended up winning 16 more games than the next-closest team in wins, the Redskins, 81 to 65, about a season-and-a-half’s worth more games won; the previous decade’s champions represented themselves well on the list, but the Eagles flew up to fourth on the list of wins behind the Packers by decade’s end, the future was now. Halas and the Bears may have re-invented the T-Formation; nearly everyone started running it by the end of the decade, and its usage and multiple mutations only increased throughout the 1950s. The other increase was the number of teams added, as the NFL now sat above 12 franchises with 13 for the first time in decades when the 1950 NFL season began with a special occasion Saturday game on September 16th, 1950, between the Cleveland Browns and the back-to-back defending champion Philadelphia Eagles.

Many sportswriters thought23 the Browns had little chance of beating the Eagles, as, after all, the Browns were only dominant because they played inferior competition, while the Eagles were the back-to-back defending champions of the premier football league in the United States, or so they thought; the Browns proved a new era was afoot with a dominant 35-10 victory in front of a crowd of 71,237 fans at the Philadelphia Municipal Stadium. The result shouldn’t have been surprising to anyone in the know, however, as the Browns, already led by quarterback Otto Graham with a supporting cast starring fullback Marion Motley and wide receivers, or ends as they were still known at the time, Mac Speedie and Dante Lavelli, all future Hall of Famers, were joined by guard Abe Gibron, defensive tackle John Kissell and halfback Rex Bumgardner in a deal before the season with the original Buffalo Bills of the AAFC, originally known as the Buffalo Bisons in their inaugural season, who all became key pieces to their ongoing success, as well as defensive end Len Ford from the Los Angeles Dons and linebacker Hal Herring, also from the Bills, in the dispersal draft following the AAFC-NFL merger. The 1950 draft also proved fruitful for the Browns, as they reloaded their depth at several positions of need and fielded seven rookies on their roster amongst the 12 overall new players when they began play for the 1950 NFL season.

Despite that overpowering display and a league-leading point differential by season’s end, the Browns were not able to lay sole claim to the league’s number-one record, as their two losses this season both came at the hands of the New York Giants, who also finished with a 10-2 record, same as the Browns. To the Giants’ credit, they revived their franchise in just one off-season, winning four more games than in 1949, thanks in no small part to rookie quarterback Travis Tidwell winning all three games he started for injured third-year starter Charlie Conerly. The third matchup between the two that season was one of two divisional tie-breaking playoff games, as the Rams and Bears also finished the season with identical records at 9-3; the Browns finally prevailed in a defensive-centric game, winning 8-3 and closing the Giants out in the fourth quarter with a field goal and a safety, while the Rams showcased their number-one ranked offense in a 24-14 win over the older Bears as Fears caught three touchdown passes and 198 of Waterfield’s 280 passing yards in the win. The Rams were back in the championship game a year after losing last season’s title game and looking to reassert the notion of NFL superiority over the Browns, getting off to a hot start with an 82-yard touchdown pass to Glenn Davis from Waterfield on the first play from scrimmage to take a quick 7-0 lead. Undeterred, the Browns tied the game with a 27-yard Dub Jones touchdown reception later in the quarter, only for the Rams to quickly retake the lead with a 3-yard Dick Hoerner touchdown run before the quarter’s close.

Showing their championship experience, regardless of how disrespected it may have been, the Browns struck back in the second quarter, with Graham throwing his second touchdown pass to Lavelli; however, a bad snap prevented kicker Alex Groza from even attempting the extra point attempt, and a rushed throw fell incomplete to maintain a one-point Rams lead. Luckily for the Browns, Waterfield threw an interception to Browns’ safety Ken Gorgal and missed a chip shot field goal before halftime to keep it at 14-13. Receiving the ball in the second half, the Browns took the lead on Graham’s third touchdown pass, a 39-yarder to Lavelli for his second touchdown reception, only for the Rams to put together a quick scoring drive capped off by another 3-yard Hoerner touchdown run. Once again facing a one-point lead, the Browns’ offense took the field only for disaster to strike, as Motley fumbled the ball, and Rams’ defensive end Larry Brink scooped it up and took a short six-yard trip to the end zone to put his team up 28-20 heading into the fourth quarter. The Eagles finished 6-6 in 1950 after getting drubbed in week 1 by the Browns; however, the Rams bounced back from defeat in the previous season’s Championship Game against those Eagles and even finished with a better record than they did the year prior, surely now, especially with an eight-point lead heading into the fourth quarter, the NFL will put the nail in the coffin of the narrative surrounding the AAFC’s darling, right?

Instead, the Browns began clawing out of that casket before the third quarter expired, with defensive back Warren Lahr intercepting Waterfield with enough time to run one more play before the end of the quarter. Graham displayed incredible poise as the Browns made three successful fourth-down conversions on this drive before Rex Bumgardner eventually hauled in a diving 14-yard touchdown reception in the back of the end zone for Graham’s fourth and final touchdown pass of the game as the Rams lead was cut to 28-27 following Groza’s successful extra-point attempt. Both defenses began to hold steady, forcing punts until the Rams began driving late in the fourth, only for Waterfield to throw another interception, this time to linebacker Tommy Thompson24, to set the Browns up near midfield. However, a couple of plays later, Graham fumbled the ball, and Rams’ defensive lineman Mike Lazetich fell on it to give the Rams possession back with roughly three minutes to play. The Browns’ defense held for one last time, though, and the Rams punted the ball away to give the Browns one last chance, starting at their 32-yard line. Graham put together a masterful game-winning drive, beginning with a 16-yard scramble up the middle before putting together a hurry-up drive starring Bumgardner and Jones, first hitting Bumgardner before connecting on consecutive completions to Jones along the sidelines, finishing with another completion to Bumgardner before one last quarterback sneak to center the ball at the Rams’ 11-yard line for Groza’s game-winning field goal attempt following the Browns’ final timeout. Groza’s field goal put the Browns ahead, 30-28, with only 20 seconds remaining; while the Rams’ final play was a Hail Mary pass attempt that the Browns intercepted, it’s worth noting they trotted out their backup quarterback for their final play, Norm Van Brocklin, at this point just a second-year quarterback who started in six games this season in place of an injured Waterfield, going 5-1 in those games before returning to the bench at the regular season’s end and scarcely seeing playoff action25.

The Browns had done it then, with then NFL Commissioner Bert Bell stating that the Browns were the “greatest team he had ever seen” immediately following the game. It all sounds like a modern-day Super Bowl event, and hopefully, if you’ve made it this far, these similarities stand out to you too; regardless, the Browns kicked off the decade in memorable fashion and were well-situated to repeat their success for the foreseeable future. Unsurprisingly, they seemed destined to do so after the conclusion of the 1951 season, as they finished with the best record in the NFL at 11-1; Graham finished second in pass completions, pass attempts, passing yards, passing touchdowns, completion percentage, and third in passer rating as the Browns also finished with the number-one ranked defense in the league that year in addition to repeating with the best point differential in the NFL.

The Los Angeles Rams again found themselves atop the opposing conference at 8-4, but this time with three teams nipping at their heels, with the Detroit Lions and San Francisco 49ers both finishing 7-4-1 and the Bears finishing 7-5. All four of these teams fell short of even the New York Giants 9-2-1 record, so what chance did the Rams have of overcoming the Browns this year, especially now after losing consecutive championship games? After a scoreless first quarter in the 1951 NFL Championship Game, the Rams did strike first again, leading 7-0 at the start of the quarter before giving up a field goal after a Waterfield interception and a 17-yard Dub Jones touchdown reception from Graham to go down 10-7 at halftime to the defending champs. They had the lead at the half last year, so with things trending downward, they could’ve easily packed it in here, but the defense held firm, and Rams defensive end Larry Brink made another big play in this game, stripping the ball from Graham, resulting in his teammate, defensive end Andy Robustelli, recovering and returning the ball down to the Browns’ one-yard line. Fullback Dan Towler rumbled in for a one-yard touchdown run to regain the lead for the Rams, 14-10, who held the Browns scoreless for the remainder of the quarter as they intercepted Graham on two of the three ensuing Browns’ possessions.

It was all coming down the fourth quarter yet again between these two teams, and after a 17-yard field goal early, the Browns put together an eight-play scoring drive that ended with a 2-yard Ken Carpenter rush and a successful Lou Groza extra point attempt to tie the game at 17. Van Brocklin entered into the game in place of Waterfield, as he had done more often at points throughout the season as Waterfield was either injured or just played poorly enough for Van Brocklin to get to the nod; he even finished with more pass attempts on the season than Waterfield in eight fewer starts and was now looking to secure not only his place as the franchise starter but the Rams’ first championship in six seasons and their first since moving to Los Angeles. Van Brocklin dropped back to pass, saw Tom Fears running wide open down the field, and delivered a strike that immediately went for a 73-yard touchdown, 24-17 Rams. There was enough time for the Browns to put two more scoring drives together, but the Rams’ defense shut them out, and their offense killed enough clock to hold on for the upset as the Rams left their home stadium that day as champions this time26. For the Browns, it was the first time in five seasons they hadn’t ended the season in whatever league they played football in as champions; it was easy to believe they’d be right back in the title picture next season, though, and if we jump ahead to next year’s Championship Game, that line of thinking wound up being correct.

However, for the first time in four seasons, the Los Angeles Rams were not their division’s representative in the NFL Championship Game, as the Detroit Lions had fully arrived amongst the title contenders with a 9-3 record. They did tie the Rams in wins and had to play a divisional tie-breaker playoff game to determine who would get the right to challenge the Browns for NFL supremacy. Still, the Lions proved their time was now in that very game, jumping out to a 14-0 lead before conceding a touchdown to make it 14-7 at halftime. From there, the Lions built on their lead to take a 24-7 lead entering the fourth quarter, while the Rams never gave up, putting together a scoring drive capped off by a Towler five-yard touchdown run and also scoring on a 56-yard Vitamin Jones punt return, all it did was make the final score of 31-21 look more respectable. For the first time in 17 seasons, the Lions were in the championship game; let’s briefly take a step back and see what it took to get here.

Buddy Parker, the head coach of the Lions at this time, was a rookie on that 1935 championship Detroit Lions team; I purposefully glossed over their title in that era to award more dramatic context to the behemoth that Parker later oversaw. The Lions were one of the premier teams of that era, primarily due to their rushing attack that consistently ranked a top-four unit in rushing attempts, rushing yards, rushing touchdowns, and rushing yards per attempt from 1933 to 1938; 1935, however, saw their passing attack top out at their highest ranking for the decade, fifth in passing yards, and a tie for their best ranking in passing touchdowns at fourth, same as 1933. The Lions used their playmakers to keep up that passing attack to a 7-3-2 record and also kept them above the 8-4 Green Bay Packers that season in a tight division that saw both the Chicago Bears and Chicago Cardinals finish 6-4-2, giving the Lions the right to face the 9-3 New York Giants; their number-one ranked defense fell to the Lions immediately, as they scored on the opening drive off the back of two consecutive completions that shifted the field and had Ace Gutowsky running in a touchdown from two yards out to take a quick 7-0 lead before the Lions ultimately won in a 26-7 beatdown that saw future coach Buddy Parker scoring the final points late in the fourth quarter27. After one more year with the Lions, they shipped him off to the Chicago Cardinals, where he spent the remainder of his career, retiring in 1943 and coming back to coach the Cardinals in 1949 before resigning at the end of the season. The Lions remained successful for another four seasons following the championship, but starting in 1940, the Lions had just one winning season, a 7-3 record in 1945, for the entirety of the decade. Bo McMilllin took over head coaching duties for the Lions in 1948 and built the team’s foundation, being responsible for the 1950 trade that brought Bobby Layne to the team but frequently got into arguments with the players and resigned following the season28. That’s how we got to this point, with the Lions entering their first title game in 17 seasons as 3.5-point favorites29 against the Browns, who were making their third consecutive NFL Championship Game appearance and seventh championship game in that same amount of time, dating back to the inaugural AAFC season.

The Lions received the opening kickoff, but neither offense amounted to much in the first quarter, with both teams missing a field goal each. Layne seized the initiative to lead a scoring drive early in the second quarter, completing two passes for 24 yards and racking up 24 of his 47 rushing yards for the game on this drive and ran the two-yard touchdown in himself to take a 7-0 lead that the Lions took into the half. The Browns came out with a chance to tie the game up immediately and were moving the ball, but Graham tossed an interception to Lions’ defensive back Jim David, halting their momentum. The Lions eventually punted, but the Browns fared no better and were suddenly down 14-0 after Lions’ halfback Doak Walker took his next rushing attempt 67 yards down the field for a touchdown. The Browns put a scoring drive together later in the quarter, capped off by a 7-yard Chick Jagade touchdown run to cut the lead in half, 14-7. For the fourth straight year, the Browns entered the fourth quarter of the NFL Championship Game with a serious chance at walking out with the title but had their work cut out against the number-one ranked defense in the league that season. That number-one defense was on full display when it mattered most, as they never yielded and even forced a turnover on downs from their five-yard line late in the quarter when the Browns were driving to tie the game up; a field goal after the fact to stretch the lead to ten, 17-7, all but confirmed the Lions’ coronation30.

The Lions had been building for a few years and were the better team in 1952, finishing one place higher on offense and defense than the Browns. In 1951, Graham was second in pass completions, pass attempts, passing yards, and passing touchdowns; the same year, Buddy Parker took over the Lions and saw Layne lead the NFL in all those same categories. Following that season, Paul Brown fully unleashed Automatic Otto on the NFL; Graham finished 1952 leading the NFL in pass attempts, pass completions, passing yards, and passing touchdowns as he led the Browns to the Championship Game. However, now the recipients of back-to-back title game losses, this most recent one coming at the hands of those Lions, it’s back to the drawing board for the Browns. Rather than rely on a sheer volume of Graham pass attempts, Brown adjusted the passing attack and reduced Graham’s pass attempts by over a hundred the following season; the result was Graham still leading the NFL in passing yards and now completion percentage, yards per attempt and passer rating as well in 1953. The results reinvigorated the Browns, who finished with the fourth-ranked offense and number-one-ranked defense that season, a spot higher than the Lions on offense and defense this season, and the league’s best record at 11-1. The Browns had the best point differential in 1953 after the Lions earned that distinction the year before, but yet, despite the Browns running away with their division, the Lions held up their end of the bargain as well and returned to the Championship Game with a 10-2 record in what became the more competitive division.

Another season, another Browns championship game touchdown concession, as the Lions put a first-quarter scoring drive together to take the initial 7-0 lead. The Browns responded with a field goal in the second quarter, but the Lions matched their efforts and went into halftime with a 10-3 lead. Of course, it would be silly to count these Browns out if you’ve read any of the prior paragraphs, so it should be no surprise to learn they claimed the momentum for most of the second half, completely shutting the Lions down while putting together a touchdown drive that Chick Jagade capped off with a 9-yard touchdown rush in the third quarter while also registering two field goals by Groza in the fourth to take a 16-10 lead with four minutes and ten seconds left on the clock. Here we go again, the Browns with minutes left in the NFL Championship Game; can they secure the win this year? No, after Groza’s touchback, Layne completed two back-to-back passes of 18 and 17 yards, respectively, before picking up four yards with his legs and delivering the tying 33-yard touchdown pass to Jim Doran down the right sideline. Doak Walker’s go-ahead extra-point attempt gave the Lions a one-point lead, 17-16, that ended up being the difference when, shortly after, Graham’s pass intended for Pete Brewster was tipped and intercepted by Lions’ rookie defensive back Carl Karilivacz. A third straight title game loss for the Browns, and the stinging fashion it occurred in is only made more severe when considering the Lions became just the sixth team to win back-to-back championships in NFL history at this point; only the third team to do so in the post-1932 playoff era.

The newspapers weren’t afraid to say Paul Brown couldn’t beat Buddy Parker31, so why should anyone expect any different when the Browns once again matched up with the Lions in the 1954 NFL Championship Game? The Browns were strong again in 1954 with a 9-3 record, with the Lions’ 9-2-1 record right behind them; the point differential between the two was minimal, favoring the Browns for the second consecutive season but only by 26 points. The Browns’ second-ranked offense in 1954 went against the Lions’ third-ranked defense, but the more intriguing matchup would be the Lions’ number-one ranked offense against the Browns’ number-one ranked defense; at least, that’s what the thought was before the game.

The game was a wild affair that started with the Lions losing a fumble on the opening drive before linebacker Joe Schmidt intercepted Otto Graham, only for the Lions to settle for three points. Unlike years past, the Browns began scoring in furious bunches following their opponents drawing first blood, with Graham throwing a 37-yard touchdown pass to Ray Renfro and an 8-yard touchdown pass to Pete Brewster before deciding to take a one-yard touchdown rush in himself in the second quarter to take a 21-3 lead. The Lions put a scoring drive together that ended with a Bill Bowman 5-yard touchdown rush to make it 21-10, but that’s as close as the Lions ever got for the rest of the game32. It was a bloodbath, with Graham throwing three touchdowns and rushing in three more for the day; Layne, the mirror opposite, tossing six interceptions. The 56-10 final score was the second-most lopsided postseason score at that point in NFL history, outdone only by the 73-0 devastation of the 1940 NFL Championship Game. What a disappointing way to lose your chance at the NFL’s ever-elusive three-peat; history tends to repeat itself33 if you pay close enough attention34. After three straight losses in the title game, the Browns had returned to the mountaintop with destructive force, looking to solidify themselves the next season with consecutive championships.

The Lions brought in three new starters for the defensive line and failed to recapture their prior success, petering out at 3-9 for the season. The Browns, however, did follow up on their championship with their sixth straight NFL Championship Game appearance and their tenth straight title game appearance when factoring in their time in the AAFC. The Browns again finished the season with the best record in the NFL, 9-2-1, and matched up against their old foes, the Los Angeles Rams, for the third time this decade. The Rams hovered around .500 in 1954 after being a top-three team in their division in ’52 and ’53, but the Lions’ collapse this season opened the door for the rest of the division; as a result, the Rams pieced it all together for an 8-3-1 record and another run at the title. I won’t waste an entire paragraph recounting that game, however, as the ultimate point is that the Browns became the seventh team ever and the fourth of the playoff era to win back-to-back championships with a dominant 38-14 victory over the Rams in the 1955 NFL Championship Game, intercepting Van Brocklin six times en route to the 24-point victory.

It’s here then where things diverge from the norm, as while the Browns remained a competitive club for the next decade, finishing the 1960s as the second-most winningest team in the regular season throughout that decade after finishing with the most wins during this decade, the Browns won only one championship in six postseason appearances from 1956 to 1969, the last season before the AFL-NFL merger. Otto Graham retired following this championship, but the changing nature of professional football also meant their defense switched from a 5-2 to a 4-3; they finished 5-7 in 1956. The Giants, still led by now 35-year-old quarterback Charlie Conerly, finished fifth and fourth on offense and defense, respectively, and claimed the top spot in the East Division in 1956 through this strong play on both sides. Meanwhile, the Western Division saw the Lions rise from their ashes to a 9-3 record, only to lose their claim to the title game in the last week of the season by losing 38-21 to the Chicago Bears, who lost to the Lions two weeks prior and just barely finished the season with a better record at 9-2-1. The Bears had several strong seasons following their 1946 championship but had always been a step behind whichever team wound up winning their division that year, even falling to the Rams in the 1950 Divisional Playoff game; drafting George Blanda in 1949 could have given this reloaded Bears roster new life, but Blanda’s injury in 1954 killed any long-term chances he had with Halas35 as the franchise quarterback.

The Bears had the number-one-ranked offense that season behind the strength of their number-one-ranked rushing attack, but the Giants shut it down in the Championship Game. Truthfully, it shouldn’t have been much of a surprise, as the Giants’ rushing defense was their strong suit, and the Bears had only the seventh-ranked defense that year; even still, a 20-0 lead before the Bears’ first touchdown in the second quarter before going down 34-7 at halftime is utterly shocking for a team with Halas’ championship pedigree coursing through it. The Giants coasted in the second half, but even still, they still scored two more touchdowns to win by a final score of 47-7; three straight ass-beatings in the title game; how exciting.

That’s football, though, and with the Giants breaking up the streak of Browns and Lions championship wins, the possibilities of next season’s Championship Game were sure to be endless. Instead, all imagination evaporated as the Browns and Lions met for the fourth time this decade to decide who would wear the crown again. It was only fair, as both teams had fully rebounded from their readjustment period to finish the season with a 9-2-1 and 8-4 record, respectively. The Lions 8-4 record tied them with the 49ers, meaning they had yet another divisional tie-breaker to settle before meeting with the Browns in the championship, and were down 27-7 in the third quarter before exhibiting that championship experience and completing the 20-point comeback to stun the 49ers with a 31-27 victory in Kezar Stadium, the 49ers’ home stadium. The Lions were back in the title game, then, finishing the season ranked sixth on offense and seventh on defense, scraping five wins together in the last six weeks based more on their experience than actual talent at this point, all without Buddy Parker, who resigned as head coach during what was supposed to be his keynote speech at a training camp dinner before the season36. Results are results, however, and they made the dance; matched against them were the Browns’ third-ranked offense, starring a rookie Jim Brown, who led the NFL in rushing yards and rushing touchdowns that season, and first-ranked defense, this challenge would be their tallest mountain to climb yet. Ironically enough, it wasn’t, as the Lions got revenge for their loss to the Browns in 1954 by blowing them out by nearly the same amount of points, just one less in this case, as they wound up winning 59-14 in a contest that was never close as the Lions jumped out to a 17-0 lead in the first quarter.

Let’s momentarily pause in consideration for these two titans of teams then, as the Browns 1964 championship is the only championship both franchises have combined to win following this season, with the Lions instead choosing to ship off Layne following their championship win and allegedly37 causing him to exclaim that Detroit “wouldn’t win for 50 years,” following the trade. The Lions finished the decade with the fourth-most wins during the regular season, falling 20 wins short of the Browns and even two wins short of the Bears, with eight wins separating them from the Giants, two franchises that, if you combine their championships for the decade, still fall short of the Lions by two. Despite that, I feel comfortable placing the Lions in contention with the Browns for the title of team of the decade, as even though there’s a considerable gap in regular season wins, all three of the Lions championships, the same amount the Browns won this decade, came at those Browns’ expense. I wouldn’t be upset with anyone disagreeing with my take here and crowning the Browns as the rightful team of the 1950s; however, I do think it’s worth considerable consideration that 48 of the Lions’ 68 wins for the decade came in the six-season span from 1952 to 1957, which includes a losing season in 1955, they shined brighter at their peak than any franchise of the era, and that’s even with two 11-1 seasons by the Browns during this decade. I say all this now because, without viable long-term solutions at quarterback, the two franchises everyone had become accustomed to being in the title picture were no longer contenders.

We live in a quarterback world now; practically every off-season sees an NFL franchise try to either draft who they believe is a generational prospect or re-sign who they trust as their franchise quarterback for a record amount of money in what’s allegedly the best method at winning a Super Bowl. In an era before Tom Brady won his seventh ring when Joe Montana and Terry Bradshaw’s four Super Bowl rings as a starting quarterback carried immense weight in casual football discussions, I remember an elderly high school coach telling me that Johnny Unitas was the best quarterback he had ever seen play. He’s easy to write off now, but in today’s world, if a quarterback got cut after their rookie season like Johnny Unitas was in 1956 and then signed with a team like he did with the Baltimore Colts in 1957, only to come in as the starter once the presumed starter went down with an injury in week 2 and finished the season leading the NFL in passing attempts, passing yards, passing touchdowns, passing touchdown percentage, yards per pass attempt, passing yards per game, and passer rating like he did, the media would rightfully hail them as the next best thing too38.

The Colts finished 7-5 in 1957; Unitas took another step in 1958, throwing fewer pass attempts and passing touchdowns overall but fewer interceptions as well, even leading the NFL in passing interception percentage and once again leading the NFL in passer rating. The Baltimore Colts, as a result, also took another step, finishing 9-3, by far their best record since joining the NFL in 1953 after the original Colts folded following the 1950 NFL season, but also finishing first in their division and tied for the best record in the NFL that season. The New York Giants and Cleveland Browns also finished 9-3 but had to play in a divisional tie-breaker to determine who would get to play the Colts for the NFL crown that season; a 10-0 stonewalling of the Browns by the Giants’ number-one ranked defense ensured they’d get a chance to try for another title against the upstart Colts in this season’s Championship Game. Truth be told, the Colts’ first-ranked offense was bolstered by their second-ranked defense that season; it didn’t matter to the Giants or the fans, as even though the Giants had the ninth-ranked offense that season, that first-ranked defense slowed down the Colts enough that the final drive of regulation, a two-minute drill engineered by Unitas, tied the game up at 17 points. This game, commonly billed as “The Greatest Game Ever Played,” even on Wikipedia, has been extensively covered by the NFL media, but to continue onto the 1959 season without telling you the Colts forced a three-and-out only for Unitas to engineer another scoring drive, this time ending in a game-winning Alan Amache goalline touchdown run when the Colts only needed a field goal to win in sudden death overtime, well, it’d be criminal of me.

In the final season of the decade then, the Colts looked to become the eighth team to repeat as champions and the fifth of the playoff era, all within six seasons of the Lions becoming the third team of the playoff era to accomplish this feat; with Unitas at the helm, the Colts looked to be in a terrific position to do so. He led the NFL in pass attempts, pass completions, passing yards, and passing touchdowns, setting the-then NFL single-season record with 32 passing touchdowns, passing touchdown percentage, and passing yards per game as he won the NFL’s Most Valuable Player award and led the Colts to another 9-3 record. They repeated as the number-one offense in the NFL, but their defense dipped to seventh out of 12 teams that season; the number-one ranked defense of the New York Giants would again test them for the crown. This time, however, the Giants’ offense improved to second behind only the Colts, as 38-year-old Charlie Conerly took a page out of Unitas’ playbook and led the NFL in passing interception percentage, taking exceptional care of the football this season. The Giants finished 10-3, first in the NFL, and had a 9-7 lead entering the fourth quarter against the Colts, allowing Unitas only a 60-yard touchdown pass in the first quarter to this point, which sounds like a lot; however, when you realize he finished the game with 264 passing yards, it becomes clear the Giants had only given up the one big pass play to that point.

Steelers head coach Walt Kiesling gave up on Unitas because he didn’t believe in his intelligence, only for Unitas to win “The Greatest Game Ever Played” and then follow up that performance by leading his team to 24 unanswered points in the fourth quarter of the following season’s Championship Game, including a 12-yard touchdown pass to Jerry Richardson before his team secured a 42-yard interception return touchdown courtesy of Johnny Sample, well, I bet Art Rooney wasn’t happy. That’s how we close the decade, with the sport’s new, flashy quarterback radiating endless possibilities toward the masses. You’ll have to forgive me for occasionally making parallels to the modern game; it just makes me chuckle that no matter how much things change, they often remain the same39.

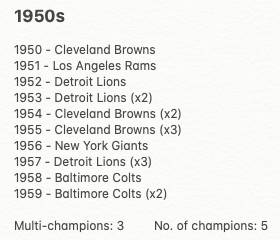

What to make of the 1950s, then? I already covered the regular season win totals for the top franchises and, in my opinion, distinguished the difference between the best team and the runner-up, so really, my ultimate conclusion about this decade is that by the end of it, everything had changed. The T-formation had become ubiquitous in professional football; by the decade’s end, teams had fully moved away from the single wing and began looking for the tiniest edges they could find in team identity, scheme, and roster construction to reign supreme over the field.

It’s here, then, where I end the essay’s historical advisement, as another competitor was born that summer, the most well-known of the American Football Leagues, but also, 1959 saw the genesis of one coach’s assault on the record books and ascension to the upper-most level of the football pantheon, a section of the NFL’s history best left for the undivided attention of a separate essay. While the NFL never looked the same following the merger between themselves and who became their biggest rival, more importantly, that coach laid the blueprint for football dominance this decade for any future team daring to chase greatness. The surname for this man became the name of the NFL’s highest honor, as the Super Bowl-winning team hoists the trophy bearing not only his name but also the immense weight of the historical significance the NFL carried up to the point of the Super Bowl becoming the massive success and cultural touchstone it has become; the Lombardi Trophy.

Editor’s Notes

- WebArchive/The Professional Football Researchers Association – 9/29/2010 – Once More, With Feeling • 1921

- WebArchive/Pro Football Hall of Fame – 9/29/2010 – Medallion from NFL’s first champions

- WebArchive/Bills Backers United – 10/11/1999 – History of Pro Football in Western New York • Who Really Won In 1921?

- WebArchive/The Professional Football Researchers Association – THE COFFIN CORNER: Vol. 2, No. 8 (1980) • CLEVELAND’S 1ST TITLE

- WebArchive/Ghosts of the Gridiron – 2/15/2009 – Pottsville Maroons • Anthracite League Champions, 1924

- Scioto Historical – The Iron Man Game of 1932

- NFL Football Operations – Bent but not Broken: The History Of The Rules

- Pigskin Dispatch – 7/11/2024 – The 1st American Football League

- Barstool Sports – 12/17/2018 – On This Date in Sports December 17, 1933: The first NFL Championship Game

- NFL/NFL 100 • Greatest Games: 62 – 1934 – Bears vs. Giants NFL Championship Game – “The Sneakers Game”

- The Washington Post – 12/2/2020 – Pandemic has disrupted football, but World War II shook up the league even more

- Pro Football Hall of Fame – The Triple Crown

- WebArchive/NBC Sports – 5/29/2017 – A history of the Bears who served during World War II

- WebArchive/YouTube – 1945 NFL Championship